Recently resurfaced photos highlight what’s often overlooked in the storied legacy of Hebrew University co-founder Albert Einstein. He was an outspoken advocate for civil rights for black Americans facing endemic racism.

By Robert Sarner, CFHU Now, June 11, 2020

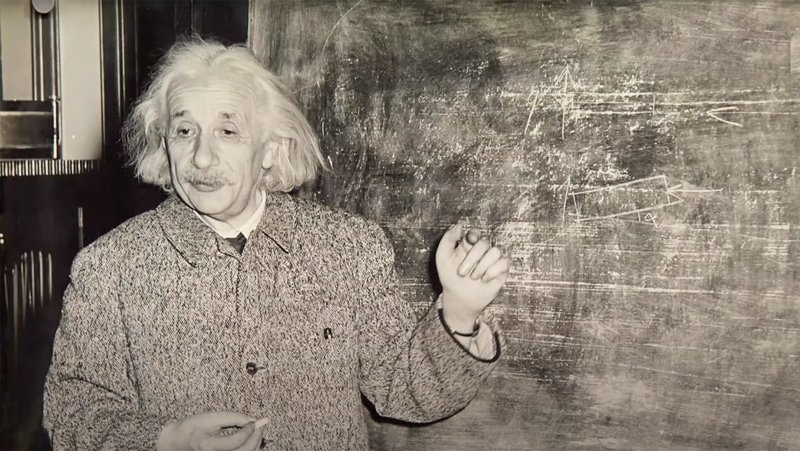

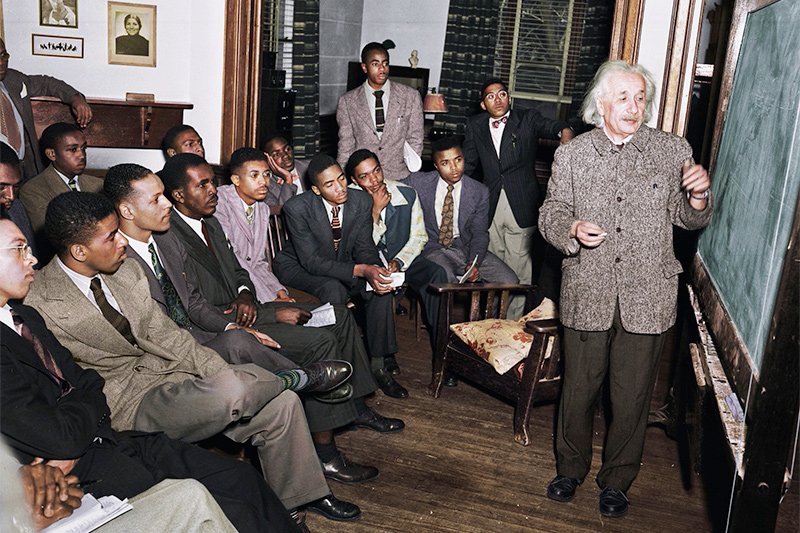

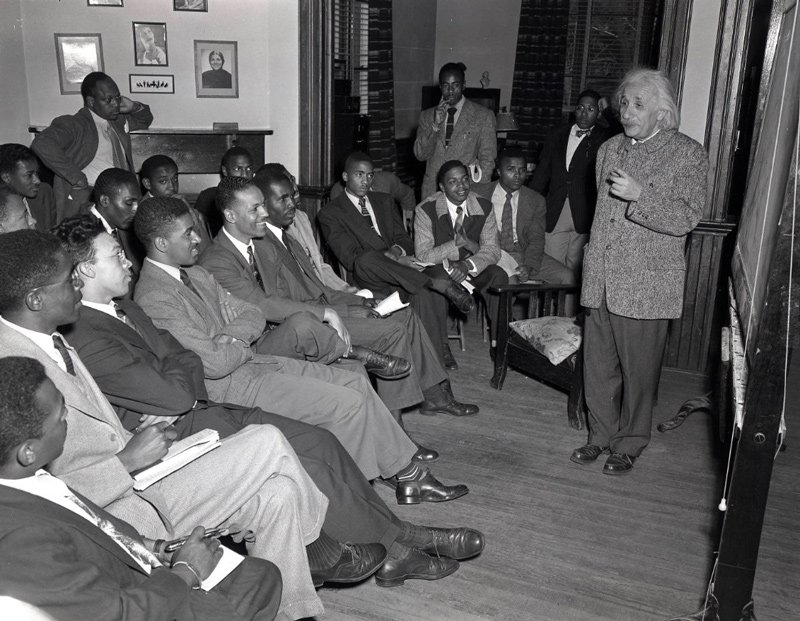

Earlier this month, amid the widespread outrage triggered by a white policeman’s brutal killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, long forgotten, rarely-seen colour photos of Albert Einstein in an unfamiliar setting began to circulate online. They showed the world’s most famous scientist and Hebrew University co-founder standing in front of a blackboard in a room with young black men dressed in jackets and ties.

At a time when the issue of anti-black racism in the United States is dominating headlines, few people would link Einstein to the Black Lives Matter protest campaign. Yet well ahead of even the civil rights movement of the 1960s, he repeatedly stood up in defence of black Americans, denouncing the systemic, deeply rooted discrimination against them. His strong words and actions 75 years ago, often overlooked in accounts of the brilliant physicist’s life, remain equally relevant today.

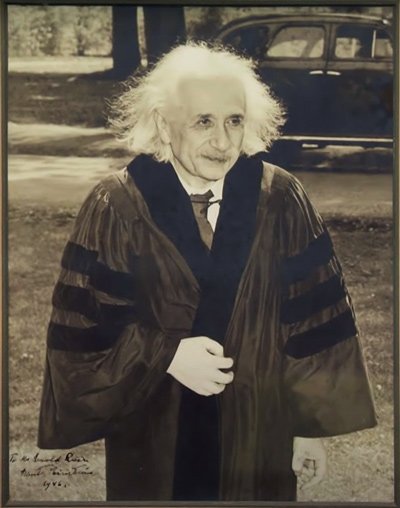

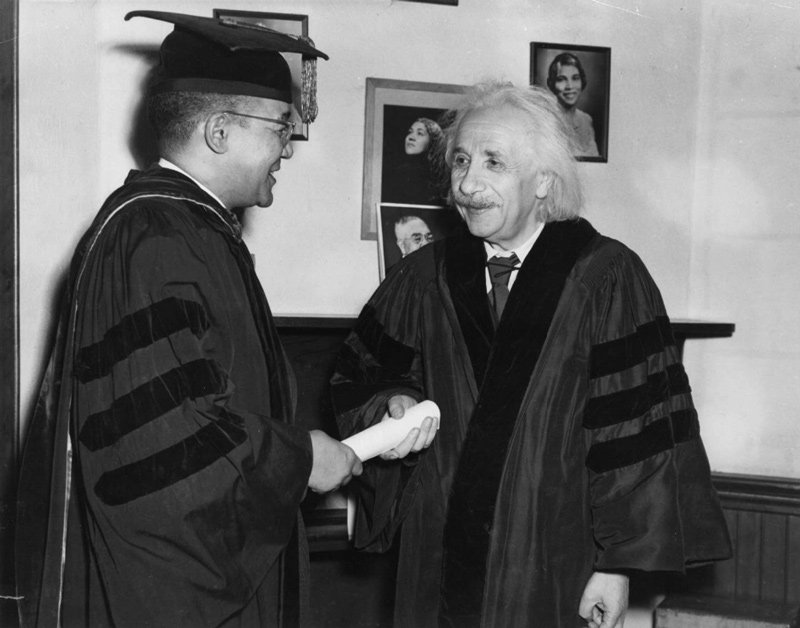

In May 1946, Einstein defied the prevailing racial climate at the time to visit Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, the first degree-granting black college in the US. As captured in the above-mentioned photos seen here, he spoke with and took questions from students and accepted an honorary degree.

At that point in his life, already in failing health, Einstein rarely accepted invitations to speak at universities or accept honorary degrees as he found the presentations “ostentatious.” He made an exception in support of Lincoln University and social justice for black Americans.

“My trip to this institution was on behalf of a worthwhile cause,” Einstein said in his address. “There is a separation of colored people from white people in the United States. That separation is not a disease of colored people. It’s a disease of white people.”

Despite Einstein’s celebrity status, his visit to Lincoln was largely ignored by the mainstream media, which usually covered his other activities.

His speech was true to the principled stance he had espoused for years. A few months before appearing at Lincoln, Einstein wrote an article titled The Negro Question in Pageant magazine in which he sharply took white Americans to task for their treatment of their black compatriots, commonly referred to at the time as Negroes.

“There is a somber point in the social outlook of Americans,” he wrote. “Their sense of quality and human dignity is mainly limited to men of white skin. Even among these, there are prejudices of which I as a Jew am clearly conscious. But they are unimportant in comparison with the attitude of whites toward their fellow citizens of darker complexion, particularly toward Negroes. The more I feel an American, the more this situation pains me. I can escape the feeling of complicity in it only by speaking out.”

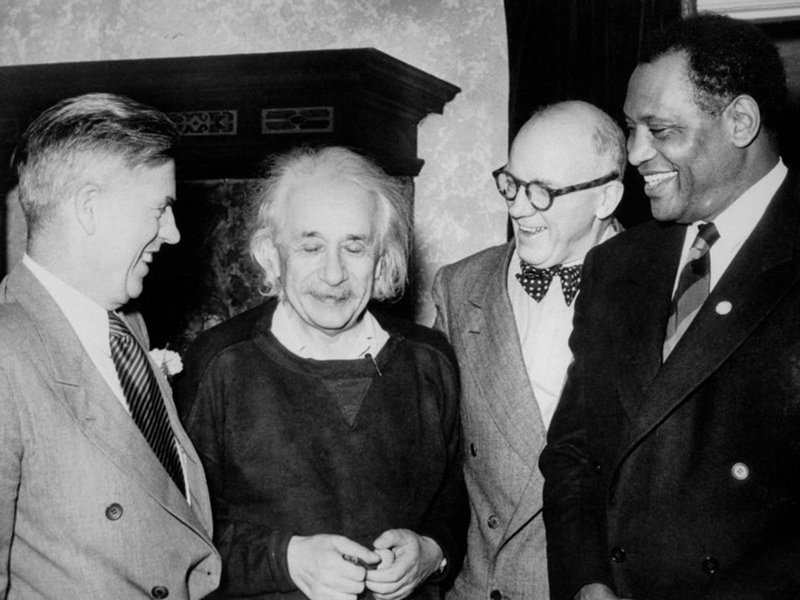

That same year, Einstein worked with his long-time friend, black actor and singer, Paul Robeson, on an anti-lynching petition campaign.

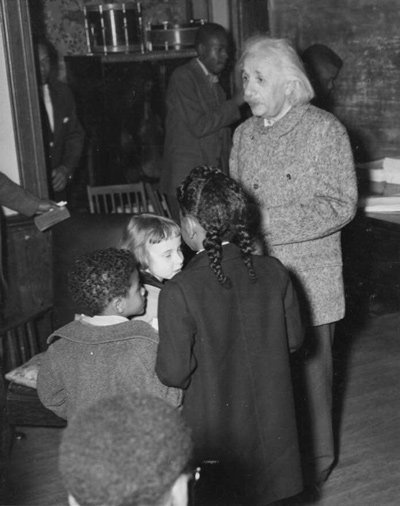

In Princeton, New Jersey, where Einstein lived, he lamented the town’s segregation and pervasive racism against black residents. His response was to cultivate relationship with members of the black community, often strolling through their streets, speaking with people and offering candy to local children.

In 1940, at the World’s Fair in New York, Einstein was asked to speak at the inauguration of an exhibit devoted to the diversity of the US population.

“As for the Negroes,” he said, “the country has still a heavy debt to discharge for all the troubles and disabilities it has laid on the Negro’s shoulders, for all that his fellow-citizens have done and to some extent still are doing to him.”

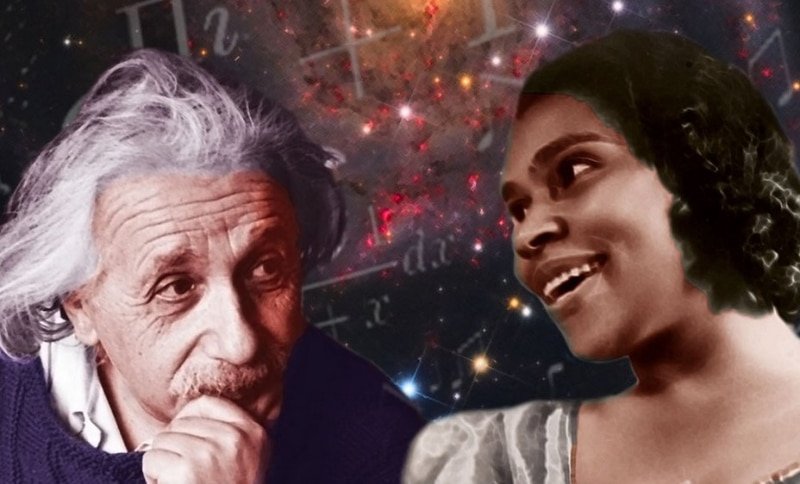

In 1937, when black opera star Marion Anderson gave a concert at Princeton but was denied lodging at a local segregated hotel, Einstein invited her to stay at his nearby home. They became friends and she often stayed at his house whenever she visited Princeton.

Einstein knew only too well of what he spoke when it came to racism. In his native Germany, he suffered Nazi-inspired anti-Semitic threats and harassment in the early 1930s as Jews were increasingly targeted with abuse. It was the rise to power of Hitler and the Nazis in Germany that caused Einstein to settle in the United States in 1933. Even before that, in 1931, he backed a campaign to defend nine black teenagers who were falsely accused of raping two white women in Alabama.

Beyond the above-mentioned acts of solidarity with black Americans, Einstein took many other initiatives during his 22 years living in the United States that demonstrated his commitment to civil rights and his abhorrence of injustice.

This isn’t to suggest Einstein was some saint-like figure. His private diaries from his travels to Asia and the Middle East in the early 1920s included xenophobic generalisations about Chinese people and others. Not to absolve him of such statements, but they weren’t intended for publication and he wrote them well before he witnessed the evil of racism in Germany under the Nazis and in the United States at the hands of white bigots.

This week, as Hebrew University announced plans for special initiatives to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Nobel Prize in physics being awarded to Einstein, it’s also worth paying tribute to his lesser-known advocacy work against anti-black racism which, all these decades later, is still sadly pertinent to the current reality.