When Islam started to spread in the seventh century, mosques were built across the Middle East, and many have endured to this day as holy places and pilgrimage sites; the most famous are in Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem, Cairo and Basra. Now it looks like Tiberias in northern Israel may be joining the list – excavations in recent years have uncovered an older layer of the city’s ancient mosque.

Katia Cytryn-Silverman of the Hebrew University, who is overseeing the dig, says this is the oldest mosque in the world that can be excavated; most ancient mosques are still being used for their original purpose.

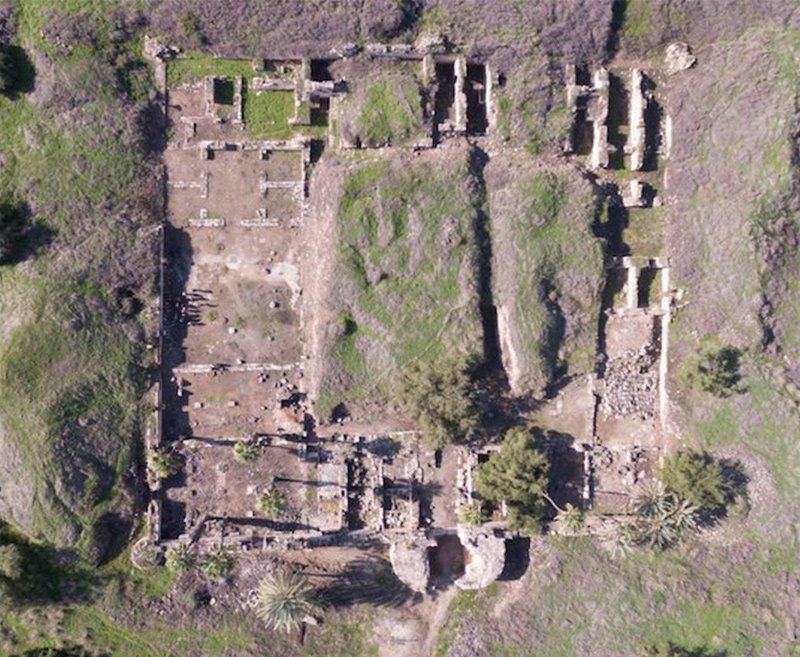

The Al-Juma (Friday) Mosque is in the south of Tiberias at the foot of Mount Berenice; the city itself is on the shore of the Kinneret, the Sea of Galilee. Before Cytryn-Silverman began excavating there 11 years ago, scholars believed that the structure at the center of the site was a marketplace from the Byzantine period. Cytryn-Silverman discovered that it was a mosque from the eighth century in the early Islamic period.

But findings in recent years have shown that under this structure is an even older mosque, dating to the seventh century. Cytryn-Silverman notes that there aren’t many chances to excavate ancient mosques because, in most cases, other mosques were later built on top of them. Such is the case with the mosque in Fustat, currently part of old Cairo and Egypt’s first capital under Muslim rule.

She says Muslim Caliph Amr bin al-As’s “first mosque in Egypt is in the same location to this day, but it has changed over the years and we don’t know what it looked like originally. The same thing has happened in Jerusalem. We also don’t know how the mosque in Medina looked; we can only theorize based on the sources that it was simple and made of palm trunks – like a big sukkah that developed more afterwards.”

Before the identification of the mosque in Tiberias, the oldest mosque to be excavated was the one in Wasit, Iraq, which was built in 703. Cytryn-Silverman made the first public presentation of her findings last week at a conference organized by the Hebrew University and the Ben-Zvi Institute to mark the 2,000th anniversary of Tiberias’ founding.

Tiberias was a very important city in Islam. After the Arab conquest, it became the capital of Jund al-Urdunn, the military district of Jordan, in the early Islamic period. Cytryn-Silverman says that during this stretch, the city was a political and economic center.

She says it connects to the Hammat Tiberias archaeological site “and spreads north; it becomes a very big city. In terms of Judaism, too, this is an important period.”

Friday mosques, which were built in main cities, were community mosques where local political figures delivered the Friday sermons. As the population grew and spread out, more and more of these structures were built.

At Tiberias, only the lower foundations remain of the older mosque underneath, and some of this was unearthed in 2004 by archaeologist Yizhar Hirschfeld. But it took years to fully understand the context of the findings. Researchers figured out the years the mosque was active with the aid of artifacts discovered in the filling beneath the floor – coins and pottery shards from the period.

Cytryn-Silverman says that the earth used as the filling was brought in from elsewhere, and that from her correspondence with an archaeologist from Yemen, she received “support for my theory that the construction technology used at the ancient mosque, a simple and pragmatic style uncharacteristic of the region, apparently first came to Israel at the start of the Arab conquest in the seventh century. It may be technology that originated in the Arabian Peninsula.”

She estimates that the old mosque was 22 by 49 meters, an imperfect rectangle with a courtyard of uncertain size, but smaller than the newer mosque previously discovered above it, which dates to between 720 and 740 and measures 78 by 90 meters.

The excavations in Tiberias are due to resume soon, in a collaboration between the Hebrew University and the German Protestant Institute of Archaeology on the Mount of Olives. The dig is set to include a structure that appears to be a small 12th-century Crusader church that was uncovered in 2018 and sits next to the mosque’s big wall not far from the ruins of Tiberias’ Byzantine church.

This church, which was in use from the fifth until at least the 10th century, was the largest in the Galilee, and scholars believe that a monumental synagogue stood alongside the church and the mosque.

“This was an area that was multireligious and a very moving symbol of regional coexistence,” Cytryn-Silverman says. “At the time that these monumental structures stood in the center of the city, the time when they were active is considered the city’s peak period. It was the time of famous and impressive Jewish activity here, including the writing of the Aleppo Codex in the first half of the 10th century.”

Cytryn-Silverman adds, “Tiberias will take off and stride toward a bright future when it takes in all of its past, with all the religions and cultures that dwelled there since the time of its founding.”