Editor’s note: Hanoch Gutfreund is a professor emeritus of theoretical physics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and former rector and president of the university. At present, he is the academic head of the Albert Einstein Archives at the Hebrew University. He is the author of several books on Einstein including ‘Einstein on Einstein’.

Next year will mark a century since Albert Einstein accepted his Nobel Prize in physics for the theories that fundamentally changed the way we understand our universe and what we as human beings can accomplish with that understanding.

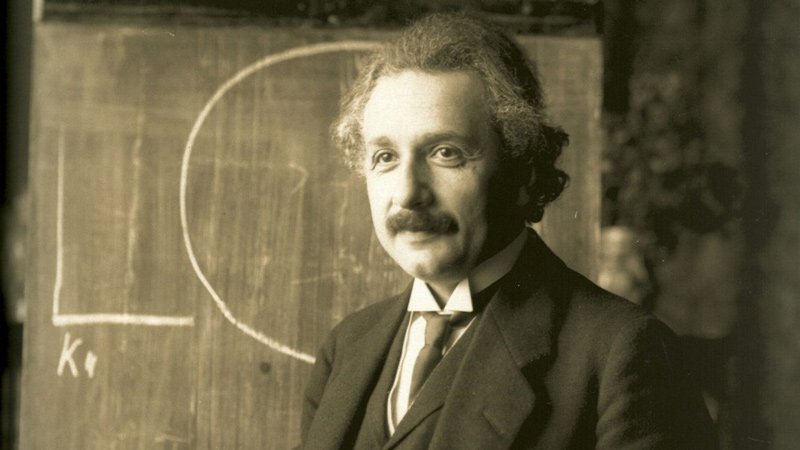

Sixty-five years after his death, Einstein remains the most recognizable scientist in history, not just because of his quirky appearance and life but because he still has lessons to teach us.

As we head into the dark tunnel of a Covid-19 winter, guided by the beckoning light of highly promising vaccine prototypes, Einstein’s strong belief in the power and necessity of global cooperation comes to mind.

In May 1946, Einstein was appointed chairman of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, which served as a platform for promoting the idea of an international framework, like the United Nations, for the control of nuclear energy.

With this appointment, Einstein began to campaign towards this goal, keeping also in mind the notion of a world government. He had already established himself as a person of conscience by speaking out against German aggression in both world wars and renouncing his German citizenship at the dawn of Hitler’s rise.

In an interview published June 23, 1946 in the New York Times, he said:

“Today the atomic bomb has altered profoundly the nature of the world as we knew it, and the human race consequently finds itself in a new habitat to which it must adapt its thinking. In the light of new knowledge, a world authority and an eventual world state are not just desirable in the name of brotherhood, they are necessary for survival. … Today we must abandon competition and secure cooperation. This must be the central fact in all our considerations of international affairs; otherwise we face certain disaster. Past thinking and methods did not prevent wars. Future thinking must prevent wars.”

An instrument of peace

On November 11, 1947, the Foreign Press Association to the United Nation granted Einstein its award for this activity “in recognition of his valiant effort to make the world’s nations understand the need of outlawing atomic energy as a means of war and of developing it as an instrument of peace.”

In his acceptance address, Einstein expressed his frustration at the failure to get his message across: “Most people go on living their everyday life; half frightened, half indifferent, they behold the ghostly tragi-comedy that is being performed on the international stage. But on that stage, on which the actors under the flood-lights play their ordained parts, our fate of tomorrow, life or death of the nations, is being decided.”

Einstein speculated that, maybe, if the threat of the survival of mankind would not be manmade, like the atomic bomb, the response would have been different. For instance, if an epidemic of bubonic plague were threatening the entire world. He then asked if the global threat of nuclear weapons is not a “situation that could be compared to one of a menacing epidemic?”

Einstein predicted that: “In such a case conscientious and expert persons would be brought together and they would work out an intelligent plan to combat the plague… they would submit their plan to the governments. These would hardly raise objections but rather agree speedily on the measures to be taken. They certainly would never think of trying to handle the matter so that their own nation would be spared whereas the next one would be decimated.”

The worst is yet to come

Today, the coronavirus is affecting every country in the world, having already infected more than 50 million people and killed more than 1.2 million. The World Health Organization warns us that the worst is yet to come.

The Albert Einstein Archives at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem constitutes an extraordinary cultural asset of universal importance for humanity. Its holdings consist of numerous original manuscripts, prolific correspondence with peers, and a large variety of additional material about Einstein.

As Einstein expressed his opinion on every important issue on the agenda of his times, the documents of the archives are a valuable resource for the intellectual, social and political history of the first half of the 20th century, and also a repository of great insights.

Through the promotion of Einstein’s legacy over the years, the archives have become intimately linked with his name. In 2021, in tribute to the Nobel Prize centennial, Hebrew University will produce Einstein: Visualize the Impossible, a digital exhibition and broad-based educational program.

Guided by advisors from some of our leading academic and cultural institutions and made possible by technology industry leaders, this digital platform will bring the theories, ideas and impact of Einstein to students and other audiences across the United States and around the world.

In particular, it will demonstrate to the public and its schoolchildren why Einstein is still so relevant today and why he is still so alive in the public eye. While other figures recede into history, public interest in Einstein has only increased.

We pray by that time the Covid pandemic will be in check. And that as we mourn the unbearable toll, we can look ahead at rebuilding together and guarding against future plagues. The Einsteins of this generation must bear in mind what his message would have been today.

We can only hope that there is still a chance that the response to his appeal today would generate a genuine international cooperation of the kind he tried to achieve 75 years ago.