As student room-mates in a foreign country, you soon learn what pushes other people’s buttons. In Tamara Rosenberg’s case, it seemed, not a lot. She did not sweat the small stuff – a valuable trait for coping with Israel’s intense vibe. “Do you want to have this for dinner?” Tamara’s flatmate, Carolyn Rubinstein, would ask of her roomie. “Yeah, sure,” Tamara would reply. “Which movie shall we go see?” “You choose.”

Carolyn, then 22, and Tamara, 20, had known each other for only three or four weeks before the morning of August 21, 1995 – the day that would bond them forever. The pair shared a room at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem after Tamara, who had grown up in Paris, and Carolyn, from Sydney, travelled to Israel to study Hebrew and immerse themselves in a culture that was, and still is, a magnet for so many young Jewish people around the world. Tamara wanted to get her skills in the language up to speed ahead of her upcoming arts degree; Carolyn was on a scholarship to learn about Israeli life and Jewish history.

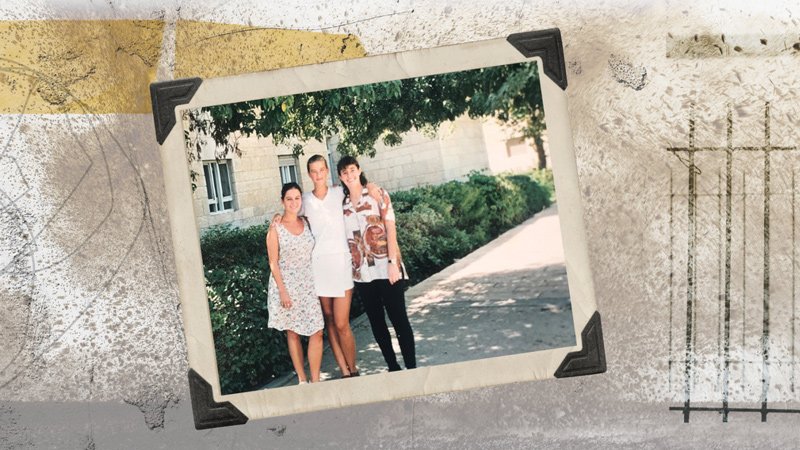

“Tamara was a very chilled personality; we used to joke that she seemed zoned out,” says Carolyn, now a 47-year-old primary school teacher in Sydney and mother of daughters aged 20, 18 and 14. We meet in my lounge room on Sydney’s north shore to give Carolyn’s middle daughter a calm space to study. Like a teacher you immediately trust, Carolyn’s manner is calm and measured as she takes out folders of press clippings and photos she has brought to help illustrate the events of that terrible August morning.

Carolyn has been preparing for this interview after a year of correspondence following our meeting at a family dinner with my wife’s cousins. (“You should ask her about her story,” they told me.)

“Our dorm was about 45 minutes away from the main campus of the Hebrew University, and the three of us would catch the same bus, number 26, each morning at about 7.30am,” she recalls. “We would always sit at the back together, the three of us. That morning, Magali said she had a sore throat and was going to the clinic. So the two of us are sitting up the back of the bus; it’s full of people, normal morning traffic, nothing out of the ordinary.

“Suddenly, Tamara says, ‘Let’s move to the front.’ I told her I couldn’t be bothered. And she says again, slowly, with an unmistakable conviction, ‘We are moving – now.’ I was so taken back by her reaction because she just never talked like that. I got up and followed her to the front.”

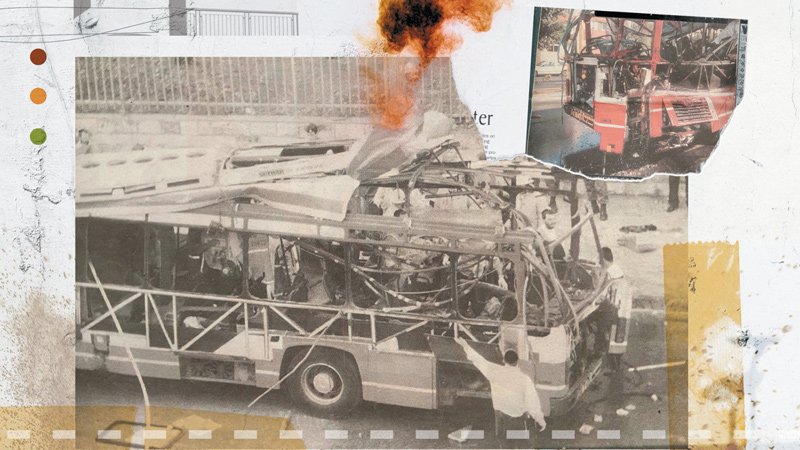

Life can change forever on such a decision. At 7.45am, five seconds after Carolyn and Tamara took their new places, their bus exploded when a Palestinian suicide bomber, sitting at the back, detonated a pipe bomb concealed in his clothing.

The explosion sent a fireball high into the air, ripped apart the rear section and was so powerful it shattered another bus the women’s vehicle was overtaking as it passed through Ramat Eshkol, a neighbourhood popular with young ultra-Orthodox families.

Four passengers were killed at the time and more than 100 wounded in the vicinity, including passengers in the second bus.

The militant Palestinian Islamist organisation Hamas claimed responsibility for the attack, as it had for a spate of bombings in the years beforehand. (The device was made by its chief bombmaker, Yahya Ayyash, who had built similar devices that killed 59 people and left hundreds injured in various attacks in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv in the mid-1990s. Israeli security services assassinated the 29-year-old in early 1996 by booby-trapping his mobile phone.)

Amid the chaos, neither woman could comprehend what had happened. “There was a huge jolt forward and the seat buckled,” Carolyn remembers. “There was screaming and smoke everywhere; as soon as it dissipated, I saw the driver lying on his steering wheel, and then he moved slightly. ‘Thank god he’s alive,’ I thought. Tamara was sitting diagonally opposite me and, once the smoke cleared, I could see her blood-smeared face with small metal and glass shrapnel sticking out of it. I was covered with blood from the shrapnel cuts at the back of my neck and scalp and my hair was singed. That’s when I realised there had been an explosion.”

“There were limbs, there were body parts, there were pieces of people everywhere. It was horrific.”

At the time, Israel stood at a precarious crossroads between hope and dread. The Oslo Peace Accords of 1993 and 1995, between the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and the Israeli government, had opened a window of optimism about an end to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by offering the Palestinians limited self-governance in parts of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Although terrorist attacks by Hamas had not reached the catastrophic level of the early 2000s, the sporadic carnage of the previous few years had seeped into the national psyche.

As the survivors recovered from their initial shock, they began rushing to get out: Israelis knew that bombers often deployed a second, delayed device to finish the job off. Tamara looked around to see Carolyn standing in front of the doors, which had buckled from the explosion. “I pushed the doors open; I don’t even remember if I pulled Tamara out,” recalls Carolyn. “Your adrenalin kicks in and this burst of energy just takes over.”

They saw the shells of the two buses, blackened and contorted, and the full gravity of the situation sunk in. “There were limbs, there were body parts, there were pieces of people everywhere,” says Carolyn. “It was horrific.”

It was a while before they could take stock of their bodies. Apart from the shrapnel in her face, Tamara, who was wearing sandals, realised her left foot was slivered by shattered glass, which hampered her ability to run. Carolyn was covered in blood; she checked her arms and legs to make sure they were all intact. But neither was badly wounded, and given what had happened, they were both incredibly lucky.

Carolyn’s first instinct was to run, and she dragged Tamara with her. But after going about 100 metres, it dawned on her that other victims might need help. “I looked back and said to Tamara, ‘We have to go help people.’ So we started running back, but at that moment the soldiers arrived and cordoned off the area.” The women sat down on the side of the road and watched as the ambulances ferried more seriously injured people to hospital. All around, people were screaming.

When Carolyn and Tamara finally climbed into an ambulance, they shared it with another very badly hurt victim, who was lying on a stretcher. At the hospital they were allowed to make calls to family and friends; following that, the young women were treated. Carolyn had the shrapnel removed from the back of her head by a doctor; Tamara had it extracted from her face. Both were told they had pierced eardrums.

Within a few hours, Carolyn was taken back to her dormitory by a friend. The president of the university visited, as did Tamara, and she was moved to the main campus, to save her from needing to catch the bus. Her new neighbouring students showered her with support, leaving offers of hot meals or invitations to family dinners outside her door. She also visited Tamara at a nearby kibbutz to which she’d moved, and where her Israeli boyfriend lived.

All of this reassured her about staying in Israel, until four days after the explosion, when she saw two young male psychologists, trained in dealing with victims of terror, and assigned by the university. At the end of an otherwise caring session, they told Carolyn, “We are going to take you arm in arm, to get back onto a bus,” as part of a “get back up on the horse” approach to trauma management.

“As the bus approached, I freaked out and started running down the road. I just could not get on the bus.”

The bus driver had already been made to drive the route again by his counsellors, the same day of the bombing, after he had been cleaned up in hospital. “As the bus approached , I freaked out and started running down the road,” Carolyn recalls. “These two counsellors were running after me; I just could not get on the bus.”

She went back to her room, collapsed on the floor in a foetal position and started sobbing hysterically. “I remember going to sleep one night a few days after that and waking up in a pool of sweat, with all these images in my head. I couldn’t breathe.” Her parents urged her to use the return ticket of the round-trip airfare she had booked. “There was no one there for me, no close family,” she recalls.

Forty-eight hours later, Carolyn touched down in Sydney, without having said a proper goodbye to Tamara, but flooded with relief. Her boyfriend picked her up at the airport and asked her to marry him on the drive home to St Ives, where her parents had settled a decade earlier after emigrating from South Africa with their three children. “My boyfriend claimed he didn’t want to get married before 30,” she says, “but when he nearly lost me, he decided to propose.”

They married early the following year, and Carolyn embarked on her career as a teacher at a Jewish primary school in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. It would be more than 20 years before she would see Tamara again.

Tamara and I are sitting in a quiet cafe on Manhattan’s Lower West Side, a couple of blocks over from the Hudson River, nestled between SoHo and Chelsea. The sun splinters through the windows as we drink tea together. Tamara is easy, engaging company, disarmingly candid but also guarded. She has checked up on my professional background. She initially didn’t want to talk to me, to again rake over the traumatic events of that day after all this time. “What’s the moral?” she asks, adding matter-of-factly, “I can’t see why anyone would be interested in what happened, all these years later.”

It was only after some gentle but persistent cajoling from Carolyn that Tamara agreed to meet me here in New York, where she has lived for 20 years, now with a partner and young son. Over this period, she has forged a successful career as a documentary filmmaker, a highlight of which was working as a producer on the miniseries OJ: Made in America, which won the 2016 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. “I do not want my life defined by one event. It happened, I got over it and got on with my life,” she explains.

After several months of silence, Tamara now explains why she changed her mind. “I felt that this exercise could help put these events in their proper place. I don’t want to use the word ‘closure’ because that makes it sound like was very raw after all these years and that’s not how it felt. But I felt like it’s worth doing, both for me and for her.”

Tamara recounts that day with vivid clarity. “I knew bombers would blow themselves up as far away as possible from the driver. I don’t remember seeing this in the news, I don’t remember discussing it. I kind of took it as fact. You become streetwise.

“I must have felt, in the back of my mind, that the back of the bus was more dangerous than the front. I just felt uncomfortable sitting there almost from the moment I sat down, but I didn’t know why. I made us move and I remember Carolyn thinking that I was being silly, because five minutes later we would arrive at our destination.”

When the bomb exploded, Tamara could not immediately grasp what had happened. “I thought people were throwing stones at us because the window next to me was broken. It was an insane thought, because the noise was massive. All I really remember is that very strange silence of the aftermath. Everything goes silent and there is this ringing thing in your ears before everyone thinks, ‘What the f… happened, and how do we get out of here?’ ”

The gravity sunk in once they were inside the ambulance. “That was a moment of shock,” Tamara remembers, “because then we realised that it was like, some people were …” Her voice quivers and she begins to cry as she relives the suffering of those around her.

By the time she called home to Paris, her mother had already, somehow, seen a media report saying that a girl called Tamara was on the bus. “We didn’t talk for long because the calls were collect and very expensive,” recalls Tamara. “Then the Israeli doctor taking out my shrapnel told me not to cry. Who does not cry after a day like that?”

Tamara’s boyfriend picked her up from the hospital and took her to his family, who lived on a kibbutz. “They took good care of me, fed me and made me talk about it. Here’s the thing: in Israel everyone has trauma, everyone has served in the military, everyone has lost people. I was telling the story over and over and they were empathetic. I was very grateful that they just got it out of me.”

As with Carolyn, the university offered Tamara the services of a psychologist. But her experience was very different. “He was a very nice guy, very warm eyes. After I told him the whole story, he said, ‘So now you’re one of us.’ It was my test of fire.”

Whether it was the psychologist, the cathartic conversations on the kibbutz, or Tamara’s character, she felt more connected to Israeli society. A month later, she made aliyah, a word that means immigrating to Israel, but also had the sense of rising to a sort of Zionist calling.

Another factor in this decision, she stresses, was her view of the bomber and Palestinian people. “There was no part of me, even that at the time, that felt like all these people living in Israel were responsible for this. That’s why I think I was able to stay there and have a good life there; I didn’t harbour hatred or resentment. I do not hold Palestinian people responsible for what happened to me. That horrific act of terror was the act of a few individuals.”

When Tamara eventually learnt that Carolyn had gone home to Australia, she felt that, despite the trauma her friend was suffering, Carolyn had done herself a disservice. “I thought that by leaving so soon, she was robbing herself of sharing it with people who really understood; the idea that if you fall off the horse you get back on. I had to ride a bus for three years after that because I did my whole undergrad at the university. It normalised something that was very traumatic.”

“Maybe she feels like I saved her life but I feel like she saved my life when she got us out of that bus.”

Over the next three years, Tamara studied for a bachelor of arts, majoring in German and English literature; her family had come from Germany and Romania, moving to France shortly before World War II. Tamara grew up speaking German, and spoke English well, thanks to a year living in New Zealand.

In 1999 Tamara was accepted into a PhD program in New York to study speech and hearing, which led her to the world of documentary filmmaking and a decade at the Public Broadcasting Service. During this period she met her partner, an American documentary film director, while working on a film about global education, and they now have a seven-year-old son. Tamara says her career in documentary was something she felt “was meant to happen. I love this life.”

Carolyn’s trajectory has been quite different. In 2005, her marriage started to disintegrate and in the process of a separation which ended in divorce, she looked for the box that had all her clippings and documents from the bombing. Up to that point she, too, had put the incident to one side and tried to move on. Her husband didn’t bring it up, nor her mother. “My mother, who is a very strong woman, gave me the message that ‘You survived, you’ll be fine.’ So I just kind of buried it.” She was also troubled by survivor’s guilt. “I didn’t do anything. It’s not like I ran into the bus and pulled 50 people out to save them.”

Small things still press her buttons. “I couldn’t go into a butcher for a long time. The blood and guts reminded me of body parts. If I get on a plane or a bus – I don’t go on a bus very often – I can tell you in two minutes what every person is wearing, who they’re with, how many bags they have. I understand now that that might be a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder.”

Ever since the bombing, Carolyn has seen Tamara as her “guardian angel”, a phrase she repeats several times. Tamara shrugs it off, preferring to downplay her role: “Maybe she feels like I saved her life but I feel like she saved my life when she bent those doors and got us out of that bus,” she reflects.

When Carolyn and Tamara parted ways after the bombing, they were not in contact again for 14 years. It might surprise some that they did not even write a letter, make a phone call or send an email, despite having each other’s contact details.

Trauma specialists, however, are not surprised. “I don’t find it odd that they didn’t have contact,” observes Dr Cait McMahon, a psychologist and managing director of the Dart Centre Asia Pacific, based in Melbourne, which investigates journalism and trauma. “There is an assumption in the broader community that people who experience significant trauma will be bonded. But by and large, most of them just get on with their lives and cope fine. There are not always deep scars of post-trauma stress. As horrible as some things are, not everyone is completely devastated by it.”

“We were so young and we had all our lives in front of us. I was not avoiding her. We were busy living our lives.”

Dr. Michael Robertson, associate professor of mental health ethics at Sydney University, says a victim’s response to a traumatic event is largely determined by what happens to them afterwards and by social acceptability. “Victims of terrorism certainly experience an array of problems, but they tend to have their experiences validated and their feelings endorsed. But other trauma victims, such as sexual abuse victims, tend to be repudiated, rejected and sometimes blamed.”

Carolyn says she has not given much thought to why she didn’t maintain contact with Tamara. “I did think about her. But we only knew each other for about four weeks before. So it wasn’t like I’d had this six-month friendship with her,” she says slowly.

Muses Tamara: “We were so young and we had all our lives in front of us. I definitely was not avoiding her. We were busy living our lives.”

Carolyn’s personal life may have kept the attack more vivid in her mind. She returned to Israel to compete in the 2009 Maccabiah Games, an event modelled on the Olympics but for Jewish athletes from around the world. A serious tennis player in her youth, she saw the Maccabiah as an opportunity to rekindle her love of tennis – and Israel – after her marriage broke up.

While there, she visited a modest memorial that had been built for the victims of the bus bombing, which rekindled painful memories. Before the trip, she’d mentioned the bombing to her three daughters but not in any detail, not wanting to scare them off ever visiting Israel. “After the trip, I took everything out. I showed them the photos; the shell of the bus. They were a little bit teary but they handled it well.”

Her return to Israel was satisfying on other levels, bolstered by meeting one of the psychologists who counselled her. “He invited me to meet him at the university and gave me a huge hug. It was a very emotional moment for me.”

Tamara had revisited Israel much earlier, in 2001, at the height of the second intifada’s suicide attacks. “I was elated to be back but avoided buses; it wasn’t worth the risk,” she says. “I have visited a couple of times since and have always done so with enthusiasm and joy. I want to take my family at some point.”]

After reading those old accounts of the bombing in 2009, it was only a short emotional leap for Carolyn to contact Tamara. “I found her on Facebook and messaged her: ‘Do you remember me?’ She replied, ‘Of course: we have a bond.’ I told her I wanted to visit her in New York – I had always wanted to take my kids there.”

In 2016, Carolyn arrived in Manhattan with her daughters ahead of their meeting with Tamara at a cafe on Broadway. “I was super-excited to see her; my daughter Samantha said, ‘What happens if we don’t like her?’ and I said, ‘Well, then, it’s going to be a very short coffee.’ ”

As soon as the two women laid eyes on one another, both were elated. “Tamara walks in and she’s like a breath of fresh air,” Carolyn remembers. “She walks in with her partner Nick and her little son, and it was beautiful.” Although the two friends did talk about the attack, there was more reminiscing than probing.

“I don’t know what one is supposed to feel 25 years after sitting on a bus and having a bomb explode.”

“Her three daughters thanked me for keeping their mother alive,” recalls Tamara, with a touch of emotion in her voice, “which took me a little bit by surprise. But that’s how that story got told in their family. It was a delightful moment. I’m not very sentimental but it was nice to see that everyone had made a life they are happy with. She had these three wonderful daughters; she saw me with my partner and with my baby, and there was a lot to be grateful for.”

The meeting also served as an emotional breakthrough of a different sort for Tamara. “I realised that, even though we had dealt with the aftermath completely differently, she had maybe dealt with it in a healthier way than I did. She felt so connected to those events, whereas I felt like it had almost happened to somebody else. I envied her for that.”

Since their reunion, Carolyn has contacted Tamara on social media every couple of weeks, just to say hello. However, they joke that most of their exchanges over the past year have been primarily over whether to go along with my meddling in their lives to write this story. “It’s like you’re our medium,” a smiling Carolyn tells me. “Maybe if she was here it would be easier. I think if I ever went back to New York on my own I would say, ‘Hey, we’ve got two hours, let’s just talk.’ ”

Tamara is more circumspect about rehashing difficult memories. “I don’t know what one is supposed to feel 25 years after sitting on a bus and having a bomb explode,” she reflects. “Of course it must have had an effect and maybe it’s invisible. It probably changed my relationship to my own mortality. I think that I lost my innocence that day. I feel like shit just doesn’t happen to others, it happens to you, too.”