A monumental wall built around 7,000 years ago to protect coastal villages from the rising waters of the Mediterranean has been identified in Israel – and so has its ultimate failure, an international team of archaeologists has deduced.

Then as now, the peoples along the world’s coasts were contending with sea level rise. Unlike now, they weren’t contending with anthropogenic contamination of the planet but the natural ebbing of the last Ice Age. They, too, didn’t just flee or drown as the roaring seas encroached. They fought back.

Not that it worked, Ehud Galili of the University of Haifa and colleagues from Flinders University in Australia, the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Hebrew University report Wednesday in PLOS One.

In an unpredictable world, building seawalls is like having a system to protect the family from lions when they’re not really hungry. If the device can’t be relied on to work along the full intensity scale of foreseeable feline appetite, what’s the point? The lions will inevitably get you.

This is what happened on the coast of the Carmel in Neolithic northern Israel around 7,000 years ago (the last gasp of the Stone Age). The village had originally been built at about 3 meters or 10 feet above sea level. But over generations, as the ocean encroached and storms would have become more dangerous, the realization evidently congealed that protection was needed.

And thus, the wall was built as a community effort, the archaeologists posit. But inevitably, as the seas continued to rise, the seawall proved inadequate and the villages along the shores drowned.

So much for that sea view

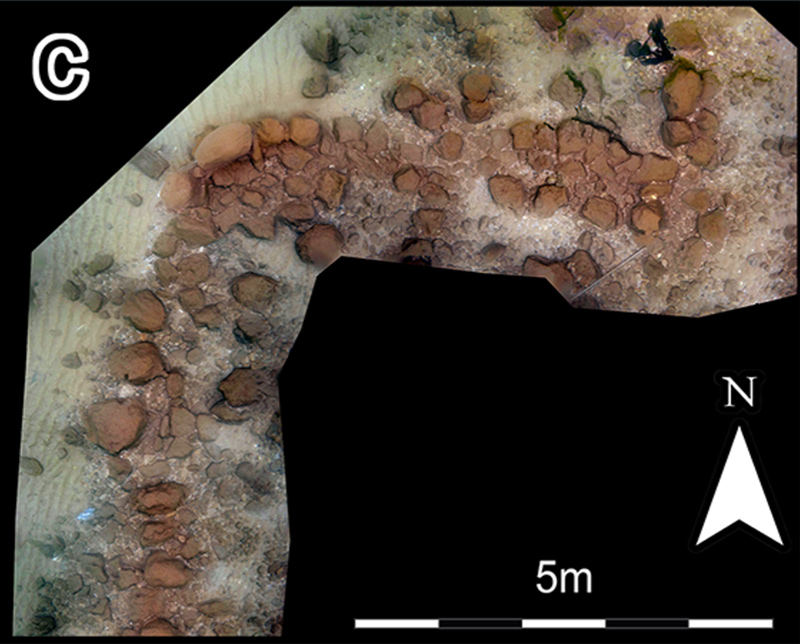

The discovery of this unique wall on the Carmel coast, stretching over 100 meters and separating the prehistoric village from the shoreline, suggests that our fight against Mother Nature’s constraints began before modern civilization.

Mean global sea levels rise and fall with the cycle of ice ages, which arrive roughly every 100,000 years. The more ice forms, the lower the seas drop – and vice versa. The last great Ice Age peaked about 20,000 years ago, since when sea levels gradually rose until the present level around 4,000 years ago. By coincidence or not, that is when the great empires began to rise around the Mediterranean basins, Galili adds.

One question is whether the Neolithic coastal folk realized the seas were not only fickle but rising over time. Galili and the team think that, up to a point, they did.

“During the Neolithic, Mediterranean populations would have experienced a sea level rise of 4 to 7 millimeters a year, or approximately 12 to 21 centimeters during a lifetime,” says Galili.

Doesn’t sound like much? Live long and prosper, they say, and if you did that in the Neolithic, you might have observed the Mediterranean rising about 70 centimeters in 100 years. By that measure, if Methuselah lived 969 years in the Neolithic, he would have experienced 6.8 meters of Mediterranean sea rise.

Still not there? Presently, global sea level is 13 to 20 centimeters higher than it was in 1900. We have noticed.

The team points out that warming weather doesn’t just cause the ocean to gently, gradually encroach on land. It increases the frequency and violence of storms. And so the team believes that the prehistoric locals would have notice the changes.

And at a spot now called Tel Hreiz, the people fought the bad temper of nature by more than wailing into the wind or sacrificing a goat. They built a vast seawall.

How can the science deduce 7,000 years after the event that they built this monumental wall to stymie the waters and not, say, Neolithic pirates or the neighbors? Because it was uniquely massive, and because of its location, Galili explains to Haaretz.

Superpower of the submerged

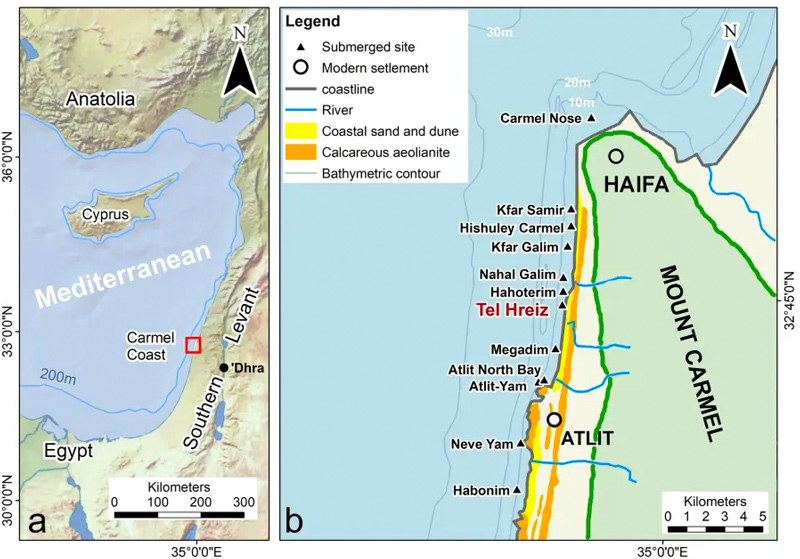

Humans have been living by the sea since the beginning. It has long been postulated that the archaeological investigation of land inundated by rising seas will find evidence of human habitation. And in the rare circumstance of its preservation, evidence has been found – especially in Israel.

“Israel is a superpower of submerged landscapes,” Galili claims. “Nowhere else in the world have remains been discovered like here.” The paper notes that the prehistoric villages were preserved by the sand that covered them as the seas rolled in.

Bits and bobs from drowned Neolithic communities have also been found off northwestern Europe, England, Denmark and Finland (in its case, inside a lake). Of particular interest to the curious are artifacts fished up from Doggerland, a low-lying bank that connected Britain with the Continent. Once occupied by people and rich in animal life, Doggerland sank underwater once and for all some 8,000 years ago.

Yet Israel is the only place where whole coastal villages from Neolithic civilizations – complete with buildings, cemeteries and wells – were found, Galili says. In a stretch of beach just 15 to 18 kilometers long, the remains of 15 villages have been found on the seafloor in a stunning state of preservation, thanks to being covered by sand.

The most ancient of that chain, at Atlit, is a pre-pottery Neolithic village about 9,000 years old. It is, not coincidentally, 200 to 400 meters offshore at a depth of 8 to 12 meters. Nearer today’s beach and in shallower water, i.e., it was submerged later, diving excavators have found villages dating back 7,500 to 7,000 years. They did have ceramic technology by then. The location of these villages demonstrates the moving shoreline as the sea level rose, Galili says.

The village at Tel Hreiz is from the ceramic period – and it featured that weird wall mentioned above.

“There are no known or similar built structures at any of the other submerged villages in the region, making the Tel Hreiz site a unique example of this visible evidence for human response to sea level rise in the Neolithic,” says Jonathan Benjamin of Flinders University.

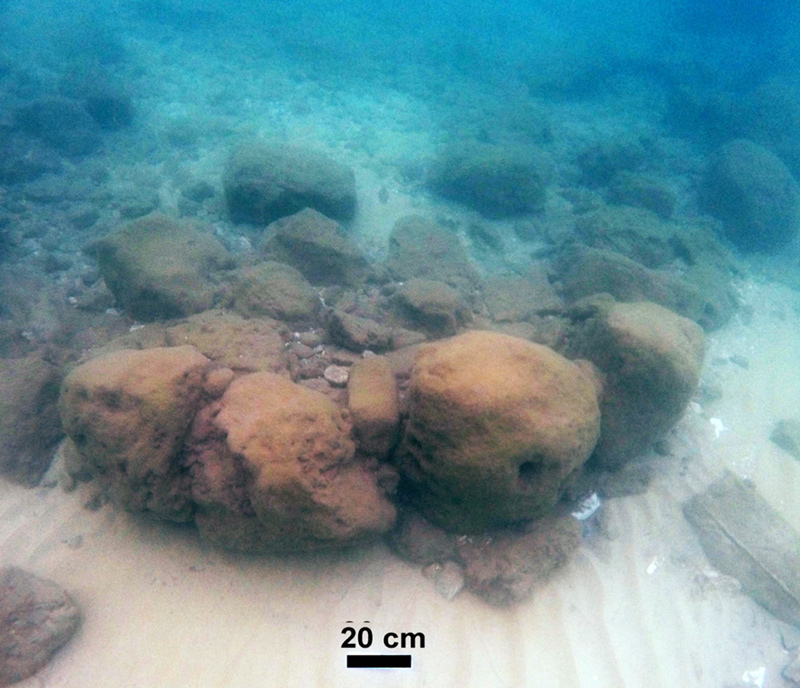

“All the other buildings in all these sites were made of undressed stones,” Galili elaborates. Also, all the other edifices – including walls and homes and wells – were made of stone blocks that any reasonably robust person could lift and move, weighing about 40-50 kilograms (88-110 pounds) each.

However, “this wall was made of boulders that could be a meter in length and weigh over a ton. No person could move this alone,” he says. The boulders comprising the wall had been brought over from riverbeds lying a kilometer or two from the village. Note that quadrupeds had not been domesticated yet, so it must have been a group effort.

The wall had a dogleg here and beefed-up section there, but it was definitely a uniform structure and wasn’t the wall of some mega-dwelling. Among other things found at Tel Hreiz were wooden posts now set firmly in the seafloor, which the archaeologists suspect were part of housing foundations.

So the monumental wall was clearly not residential and was nothing like the edifices related with worship that were found at the other sites.

For instance? “At Atlit Yam, we found a small ‘Stonehenge,’” Galili says – a circle a few meters in diameter, demarcated by standing stones.

Further suggesting that it protected the villages from the sea and not hostile tribes: “We found no signs of conflicts or walls like Jericho,” he says.

Finally, the Tel Hreiz wall now found 3 meters below sea level is very similar to another found from Bronze Age Atlit, albeit from 3,000 years later, which the archaeologists believe was built to protect a village in Atlit Bay.

We know the wall failed because the village had to be abandoned as the sea continued to rise, for another 3,000 years. All that remains are the skeletal bodies of two young women, hundreds of olive pits – begging thoughts of olive oil production – and bones from cows, pigs, goats and dogs. And some deer. The archaeologists think the village was occupied for around 500 years, after which the residents could either grow gills or leave.

“I always say we have adaptation versus evacuation. That is the state of affairs today, and that is what they experienced 7,000 years ago,” Galili says.

If you’re under threat from rising seas, you can build and build and build – but at some point it doesn’t pay. The investment in construction is too great, and if one nasty storm boosts the seas to leapfrog over that wall and drown the sheltered town, all that investment is for naught.

Nowadays, we have tamed the horse, the wolf and the hamster, we can peer into the farthest reaches of the universe or, closer to home, see individual atoms. But we are still building seawalls. Not only that, we are doing so under the very conditions that rendered them futile some 7,000 years ago: Sea level isn’t stable; it’s rising, and future sea level rise is locked in even if we stop emitting carbon today. Which we aren’t about to do.

Maybe we should take a hint from the Dutch, who after centuries and generations of combating the (stable) seas, called it a day. A new day, that is: The new Netherlands policy is adaptation and to learn to live with the rising, violent seas.