Israeli researchers say they have developed an intravenous injection to fight hospital superbugs — bacteria that are resistant to most current antibiotics.

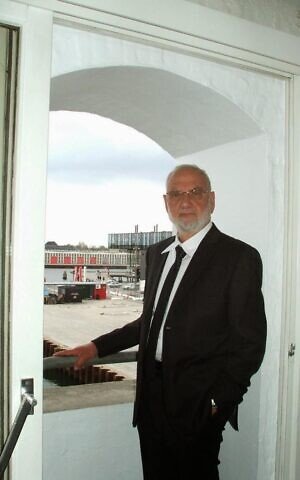

Yechezkel Barenholz of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Faculty of Medicine and Hadassah Medical School, told The Times of Israel that the treatment is a “game-changer” in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

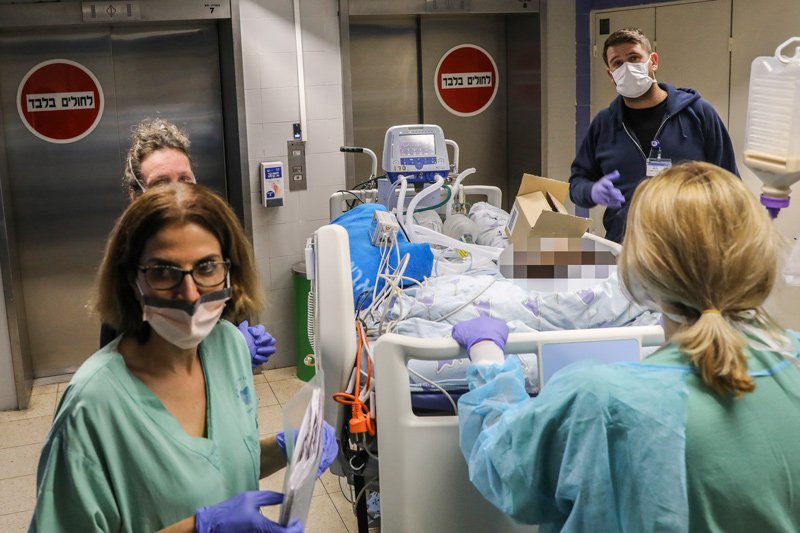

The treatment could be particularly useful as the world fights the coronavirus pandemic, with many patients developing secondary bacterial infections.

A study published in The Lancet, a top British medical journal, monitored a sample in which one in two coronavirus patients who died had developed a secondary infection.

“Coronavirus patients are often given antibiotics as a preventative measure, but there are still cases of infections from bacteria that have developed resistance to antibiotics,” said Barenholz, who heads the Hadassah Medical School’s Laboratory of Membrane and Liposome Research

While coronavirus patients are particularly vulnerable, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are a general concern of doctors. They are a major threat to global health, according to the World Health Organization and the US Centers for Disease Control.

With funding from America’s National Institutes of Health and the help of Germany’s Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research, Barenholz’s team used nanotechnology to develop an injection form of mupirocin. It reports that the common topical antibiotic drug, often sold as Bactroban ointment, has shown unusually strong abilities to fight superbugs.

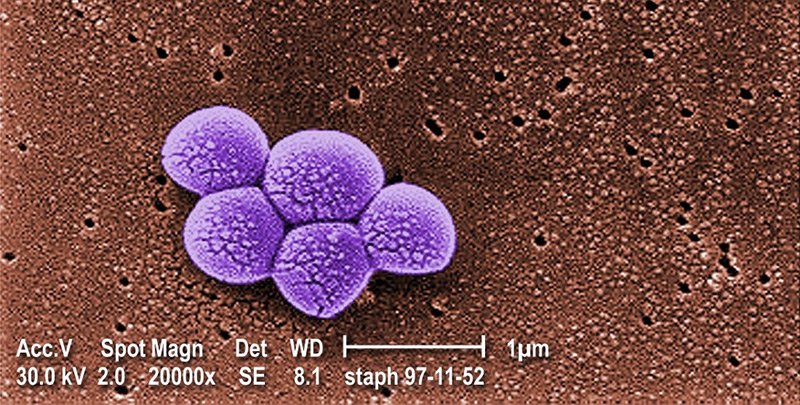

“We found people who are infected by bacteria that are hard to treat with other drugs, then infected animals with their bacteria, and successfully treated the animals using this drug,” said Barenholz. The bacteria tested included a strand of gonorrhoea for which an antibiotic has not yet been identified, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, which responds to a limited range of antibiotics, that are prone to side effects.

Barenholz commented: “It’s very exciting given that we’ve treated a bacteria that is resistant to all antibiotics but isn’t resistant to this drug.”

He said that mupirocin has long been known for its strong antibiotic qualities, but as it could only be rubbed on the skin, had limited use for treating hospital infections. “The drug we worked on is the same but we changed the way it is delivered, enabling it to be injected,” he said. “Now it can be used selectively, to reach the tissue of the infection.”

This was a hard process because, without intense modification, mupirocin normally dissolves as soon as it is injected into the body.

The reformulated drug is called nano-mupirocin, because of complex nanotechnology used in the process.

It involved enveloping the drug in a human-made liposome, which Barenholz describes as a “very small ball, a nano ball, with a shell, water in the inside, and the drug inside the water.” It also includes a mechanism which is akin to a “tiny pump” that “sucks the drug in very high concentrations to exactly where it needs to go.”

He said that this advanced method for administering the drug makes it unlike most other antibiotics, and predicted that it will mean that if bacteria develop resistance to his drug, it will be a slow process. He explained: “Because the antibiotic is in a liposome, the body has less exposure to it than is normal to antibiotics, therefore resistance would grow more slowly.”

Barenholz said that the injection is being prepared for clinical testing, and it could be approved within four months. “The hope is that when there is a second coronavirus wave, this will be a tool of physicians to prevent the impact of resistant bacteria.”