A new study has discovered a connection between climate patterns and the patterns of flu outbreaks in the Middle East.

The study, conducted by researchers from Israel, Jordan, the Palestinian Authority and Germany, showed that climate data can help predict – at the level of weeks, months and even years – when the virus will erupt each year, when it will peak and when it will subside.

It also showed the potential of cooperation between climate scientists and public health experts for understanding how different diseases behave over the course of the year, as well as the influence of climate on human health in general.

The research was published last week in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

Flu viruses are highly affected by the season, which is why they are called “seasonal flu.” Moreover, studies have shown a connection between the behavior of the virus and various climate variables, such as temperatures and rainfall, according to Prof. Hagai Levine.

Levine is an epidemiologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s school of public health and Hadassah Medical Center in the city; he is also head of the Israeli Association of Public Health Physicians.

The problem is that it’s almost impossible to predict what the temperature will be or how much rain will fall more than a week or two in advance. But the models used by climate scientists are capable of providing a fairly accurate forecast of likely changes in weather systems in a particular locale even far into the future.

Assaf Hochman, a climatologist who is currently doing postdoctoral work at Germany’s Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, explained that Earth’s climate is a chaotic system. This makes it impossible to predict how individual variables like temperature or rainfall will behave over time.

But after decades of research on chaotic systems in general, and weather in particular, climate scientists have proven tools for investigating broader changes in the weather (known as climate systems or weather systems).

The names of weather systems characteristic to specific regions are familiar to anyone who follows weather forecasts. Hot, humid hamsins in the summer are due to the Persian trough. The low pressure systems of the Israeli sharav cause hot dry weather, especially in the spring.

The extreme heat in Israel over the past two weeks developed because of the Red Sea trough, which can cause either unusual heat waves or brief, powerful storms and floods in southeastern Israel. Winter storms arrive with the winter’s low pressure systems.

Characteristic weather systems are responsible for what forecasters term “normal seasonal weather.”

Advanced flu-monitoring system

The tools we have today, Hochman explains, make it possible to say fairly accurately how and when weather systems will change, even years in advance. The margin of error increases the further ahead the forecast extends. So, it’s possible to predict winter precipitation levels, even if we can’t say how much rain will fall during a particular rainy season.

No systematic effort had ever been made before to understand how these weather systems are related to outbreaks of seasonal illnesses, he adds.

For the study, the researchers used the wealth of information collected and published over the past 20 years by the Israel Center for Disease Control. One particularly important database was compiled by reports to Maccabi Healthcare Services by a small number of participating physicians, who reported, on a weekly basis, patients who presented with “flu-like symptoms” such as a fever or a cough.

To understand how many of these so-called flu-like illnesses are indeed caused by seasonal influenza viruses, the researchers were aided by so-called sentinel clinics, where laboratory samples from patients reporting various symptoms are collected and tested for the pathogen responsible for each person’s illness.

By comparing these two sets of data, the researchers were able to determine the proportion of patients with flu-like symptoms who had been infected by a strain of one of the seasonal viruses, and to get a fairly accurate picture of influenza outbreak patterns for the various years.

Israel’s flu-monitoring system is among the most advanced in the world. Furthermore, as a result of the digitalization of the country’s health care system, beginning at the turn of this century, the medical documentation of all Israelis is gathered in the central databases of the health maintenance organizations rather than being spread among a large number of different bodies, as in many other countries. After removing all patient-identifying information, the Health Ministry publishes this data, making it available to researchers.

The study, carried out as a project of regional cooperation, also sought to discover the patterns of influenza outbreaks in neighboring countries and territories. Since neither Jordan nor the Palestinian Authority maintains medical databases of a similar quality, the researchers turned to Google Trends for information about Israel’s neighbors. This tool, beloved of public opinion researchers, analyzes the popularity of various search terms in Google Search across languages and regions, over time.

These analyses suffer from certain limitations. In the context of public health, for example, global media coverage of an outbreak in one country of a particular disease might increase the number of searches of related terms in other places.

To validate the use of Google Trends, the researchers first examined the relationship between searches for words and terms connected to influenza in Israel and the clinical data in the medical databases. After establishing that changes in the popularity of search terms in fact tracked with occurrences of flu, the next stage was to determine the patterns of seasonal flu in Jordan and the PA since 2000.

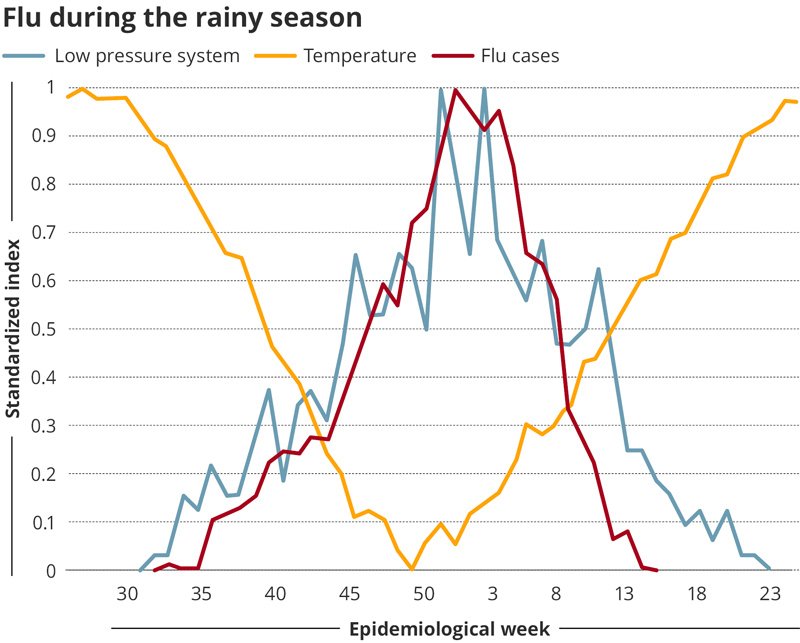

After comparing the databases of weather regimes and of seasonal flu patterns from 2008-2017, the researchers saw there was a strong correlation between the occurrence of a winter low-pressure weather regime – Cyprus lows – and seasonal influenza in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Once this was established, they used the same model for the 2004-2007 period, and determined that it held. Thus, it was possible to predict the behavior of seasonal influenza in those years.

“There are many other variables that influence the behavior of the virus. But we found very strong correlations between the climate and the illness. Our study shows that it would not be correct to ignore the climate. Even in chaos, patterns can be found,” Levine says.

The ability to predict the onset, the peak, the severity and the end of a flu outbreak in a particular region every winter could help health care providers to better prepare beforehand. For example, it can help in timing vaccination campaigns, and in readying clinics and hospitals for the expected numbers of patients.

Levine notes that the coronavirus pandemic also showed there are additional actions that could be used to reduce the spread of flu, based on such predictions. “For example, we could recommend to the public to wear masks in January,” he says.

Hochman adds that the study is proof-of-concept for using the tools of climate research to benefit public health. He says the approach could be applied to other regions and climate-sensitive diseases. He also notes that the models developed by his team could be used to better predict outbreaks of other diseases and pathogens that are seasonal, such as certain digestive disorders.

Severe data shortage

The research is also an example of the wider potential for studying the relationship between climate and epidemiology. It was carried out in the framework of a research center, established at Israel’s Arava Institute for Environmental Studies – whose participants include scholars from Israel, the PA, Jordan and European states. One of the goals of the center is to study the effect of climate change on public health and thereby to improve the ability of health organizations to contend with the expected changes.

Additional participants in the study were Prof. Pinhas Alpert of Tel Aviv University, Dr. Maya Negev of the University of Haifa, Prof. Ziad Abdeen of Al-Quds University in the West Bank and Prof. Joaquim Pinto of Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

“There’s a great shortage of scientific information about the connection between climate and public health in our region, in regard to two topics,” Hochman explains.

The first is how climate change will affect infectious illnesses such as diseases transmitted by vectors such as insects. The most famous recent example of this is the northward spread of the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, which is known to be a vector for the transmission of many viral pathogens, including the yellow fever virus, dengue fever and Chikungunya fever.

The second topic is the effect of extreme climate events on public health. “We know that people die in heat waves, but there’s no way to know to a high degree of accuracy in Israel today how many people died in a particular heat wave,” Hochman says. In Europe, he adds, the subject has received much attention since the great heat wave of 2003, which caused more than 70,000 deaths across the Continent. Even this figure was determined with the help of scientific information that was gathered in Europe afterward.

In our region, say Hochman and Levine, the information and scientific tools that are currently available are much more inadequate. The Health Ministry doesn’t have a single climatologist, and no one has been put in charge of preparing for climate change, Levine notes.

“We must increase the investment in preparing for the climate crisis, whose effects are already being felt,” he says.