Martin Buber’s “I and Thou” has become a cult classic of modern Western theology in the years since it was first published in Germany, nearly a century ago.

The book took intellectual and spiritual inspiration from Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, Taoism, and a whole host of post-Enlightenment Western secular thinkers such as Friedrich Nietzsche, to argue that there is an ethical dimension to life. Buber attributed this dimension to something above man. He called the dimension “transcendent” reality, and believed it takes place though continual dialogue with both our fellow human beings and a higher power.

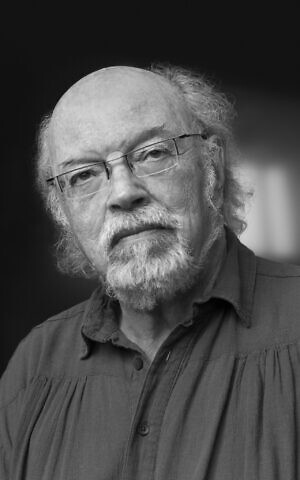

Paul Mendes-Flohr, a professor of modern Jewish thought at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, says the central theme running through almost all of Buber’s theological and philosophical thinking can essentially be whittled down to two key ideas: that the fundamental premise of all spirituality is not about religious dogma but everyday human experience, and that existential trust is the fundamental concern of every human being.

“Buber was by the idea that the Hebrew word for faith is trust,” says the 78-year-old Mendes-Flohr.

He notes how Buber’s obsessional fixation on trust may have its roots in a complex psychological coping mechanism that arose from an early childhood trauma.

“The existential scaffold of Buber’s thoughts go deeply into his experience as a three-year-old when his mother left his father to live with a Russian officer,” says Mendes-Flohr. “Buber felt deeply hurt by his mother right up until the end of his life because she never told him why she was running away.”

“Buber understood how essential healthy human relationships are for the nourishing of a full life because he failed from a young age to have the unconditional love of his mother,” Mendes-Flohr continues. “He eventually came to the understanding that unconditional love is the love we have between ourselves and God.”

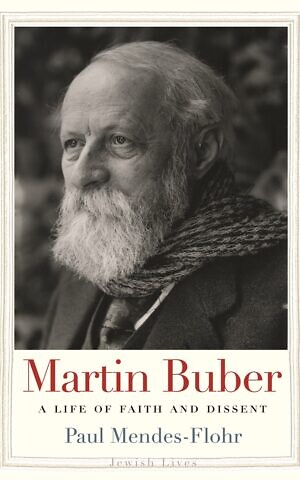

Mendes-Flohr is also an emeritus professor at the University of Chicago’s divinity school. He has written, co-authored, and edited numerous books on Jewish history, Jewish modernity, and Jewish identity and culture, including, “The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History”; “German Jews: A Dual Identity”; and “Gustav Landauer: Anarchist and Jew.”

The Jerusalem-based Jewish scholar’s latest tome is “Martin Buber: A Life of Faith and Dissent.”

The book is more of a distillation and rigorous deconstruction of Buber’s intellectual life than a straight-up biography. But it also follows a pattern that many biographers take when trying to probe the mind of a great writer and thinker — namely, trying to distinguish between the life and the work, while subtly acknowledging that without the color and complexity of one, you cannot have the richness and depth of the other.

With his constant emphasis on a universal spiritual dialogue with God, Buber took a great deal from other religions as well as from Judaism.

“Buber was very much influenced by Buddhism, which he felt had a type of spirituality that lets us address the world in every situation,” Mendes-Flohr says. “The Buddhist streak in Buber’s thought focused on the difference between hearing and listening, that listening is a spiritual and existential act.”

Buber was regarded as a pioneer bridge builder between the Christian and Jewish faiths too, often looking for similarities where others only saw divisions.

“Like many early Zionists, Buber felt that Jesus was part of the Jewish tradition,” says Mendes-Flohr. “Jesus, after all, was a Jew, and part of Jewish spirituality.”

“There is nothing foreign about Jesus’s teaching, but it’s the message of Christ which brings Jews outside of Jesus’s teachings,” Mendes-Flohr adds. “Buber felt Jesus of Nazareth and Jesus of the early gospels was deeply part of Judaism, but that it was Paul who brought the teachings of Jesus outside of Judaism.”

Why a famous German Jew felt himself to be Polish

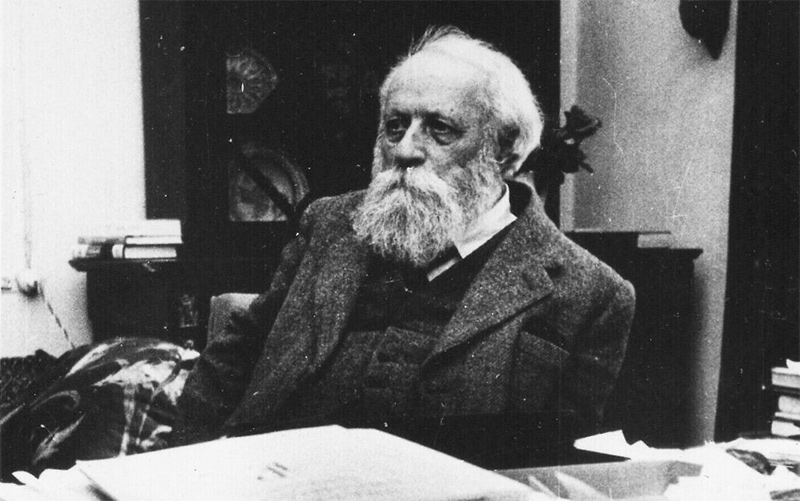

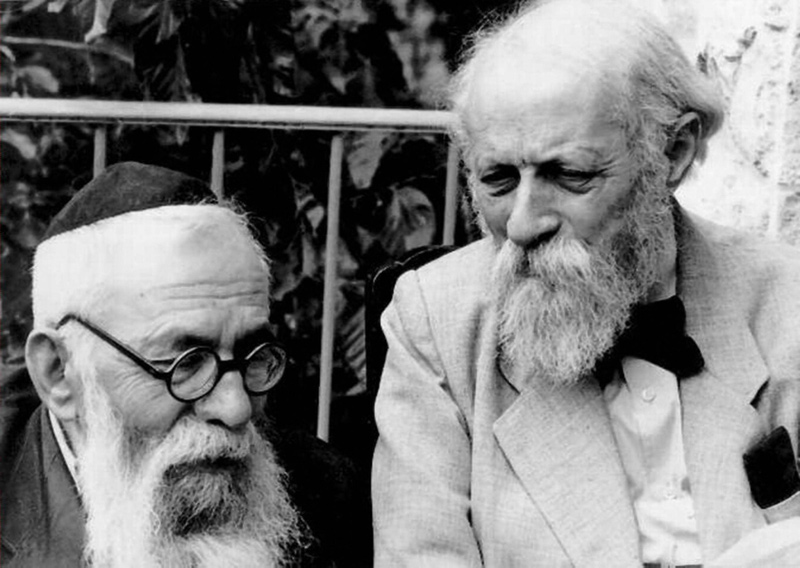

Buber was born in Vienna in 1878 and is often hailed as one of the most important spiritual thinkers and philosophers of the 20th century. His translation of the Hebrew Bible into German, which began with his friend Franz Rosenzweig, is considered a landmark cultural achievement. In 1953 Buber was awarded the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade as well as the Israel Prize for the Humanities.

Scarred by the wounds of a troubled childhood, Buber could often appear self absorbed, pompous, and narcissistic, claims Mendes-Flohr. Soon after Buber’s mother abandoned him he was sent to live with his paternal grandparents in Lemberg.

Today Lviv, Ukraine, the city was then the administrative capital of the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia, and had a vibrant spiritual, cultural and economic Jewish life that was later to be almost completely wiped out in the Holocaust.

“Buber was often cast as a German Jew because he was published mostly in German and most of his intellectual life was in Germany before coming to ,” says Mendes-Flohr. “But he always insisted that he was a Polish Jew, and he spoke Polish and Yiddish with his grandparents at home.”

Buber came to public prominence among Central European itelligentsia in his early 20s. A turning point came with a letter Buber received in November 1908 from Leo Herrmann, who was then the newly elected chair of Bar Kochba, the Association of Jewish University Students in Prague — a group of Jewish intellectuals that included Max Brod, Hans Kohn, and Robert Weltsch. The group would later become collectively known as the “Prague Circle.”

Its members were strongly interested in cultural Zionism and a vision of Jewish strength. Herrmann’s letter asked Buber if he could “remind a largely assimilated public in Prague their Judaism.”

The result was three lectures entitled “Three addresses on Judaism,” delivered between January 1909 and December 1910. “These students were not anchored in traditional Judaism, but they had a huge interest in gaining access to the spiritual core of Judaism, and Buber was their guide,” says Mendes-Flohr.

A peripheral member of Bar Kochba at the time was a relatively unknown and diffident Prague writer named Franz Kafka — an assimilated Jew with a spiritual curiosity who had no access into this world of traditional Judaism, either from his family or immediate social circle.

Mendes-Flohr believes that Buber’s spiritual mentoring of Kafka had an enormous impact on his writing. This is most noticeable in “The Trial,” with its vision of God as impotent Judge, which Kafka subtly lifted from Psalm 82 and reworked into the narrative arc of the novel where the leading protagonist, K, is condemned to death for doing nothing wrong, committing no crime, and breaking no moral code.

Indeed Kafka was so haunted by this biblical image of God as ubiquitous judge that after he first read the psalm he impulsively boarded a train from Prague to Berlin to discuss it at length with Buber.

“Kafka had a feeling that all human beings are accountable to something higher than themselves, but to whom, and to what criteria, he couldn’t figure out,” Mendes-Flohr says. “The dilemma he faced was that he didn’t know who the judge is, and so he sought counsel in Buber on this matter.”

The secular Jew who knew the Hebrew prayer book by heart

Mendes-Flohr believes it’s important to set Buber’s own cultural background against the historical and political background in which the Prague lectures and cultural conversations were set. A spiritual and political home for the Jews was still a utopian pipe dream. Moreover, many Central European Jews were imperial subjects of the Habsburg Empire, which brought its own set of cultural conformities.

“Buber was not a typical assimilated Jew; he had a strong background in traditional Judaism, he knew the Hebrew prayer book by heart, and could read all the classical texts in the Hebrew language,” says Mendes-Flohr. “And so the task he set himself was to translate traditional Judaism into the language, concerns and sensibilities of the modern world.”

Conversely, Prague-based Jews were not as well versed in the traditional spirituality of Judaism because they were all citizens of the progressive, modern, cosmopolitan and multi-political Austro-Hungarian Empire.

“This is a crucial aspect to understanding Buber’s work,” Mendes-Flohr says. “He was an Austro-Hungarian Jew, and this was why the ideas of Zionism — a state for the Jews alone — in time became problematic for Buber.”

“Buber believed Judaism flourished in the Diaspora because it lives with other cultures,” the biographer adds.

Mendes-Flohr says Buber would remain throughout his life an “atypical Zionist” who consistently took the side of spiritual Zionism when the sharp division between politics and theology regularly rose to the surface of fiery public Jewish discourse on the topic.

“Buber felt Zionism’s constant emphasis as a political movement to liberate the Jews from the scourge of anti-Semitism tended to obscure the more fundamental project of Zionism, which was the spiritual, ethical, and cultural renewal of the Jews within the content of the cosmopolitan world in relation to the divine law, the Torah,” says Mendes-Flohr.

“Buber also felt that the emphasis on the political project of establishing a state where the Jews would be secure from anti-Semitism was myopic, and would only lead to the further isolation of the Jews and to spiritual and political suicide,” he says.

“Buber was a very passionate Jew, but also very universal in a humanistic sense,” Mendes-Flohr adds. “He felt that every human being should be understood on their own terms, regardless of their background or religious beliefs.”

Israel means ‘program of war with our Arab neighbors’

Buber arrived to Mandatory Palestine from Nazi Germany in March 1938 and would remain in Israel until his death in 1965. The biography points to numerous examples of Buber’s continual efforts to offer an olive branch to the Arab population in Palestine and then later in the State of Israel.

Promoting reconciliation and peace did not always go down well with Buber’s fellow Jews, though, especially during the formative years of the State of Israel when the future of the country looked uncertain.

Two weeks into Israel’s 1948 War of Independence, for instance, Buber wrote an article where he declared that Jewish sovereignty effectively meant a continual “program of war with our Arab neighbors.” Buber also wrote at the time that the political Zionism taking place under the leadership of Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, “blasphemes the name of Zion.”

“Buber was a contested figure in Israel who constantly gave lectures, made protests, and wrote newspaper articles on issues which he felt were misguided in Israeli politics, particularly with respect to the Arabs,” says Mendes-Flohr. “But even when he had a public confrontation, it was always met with a certain respect .”

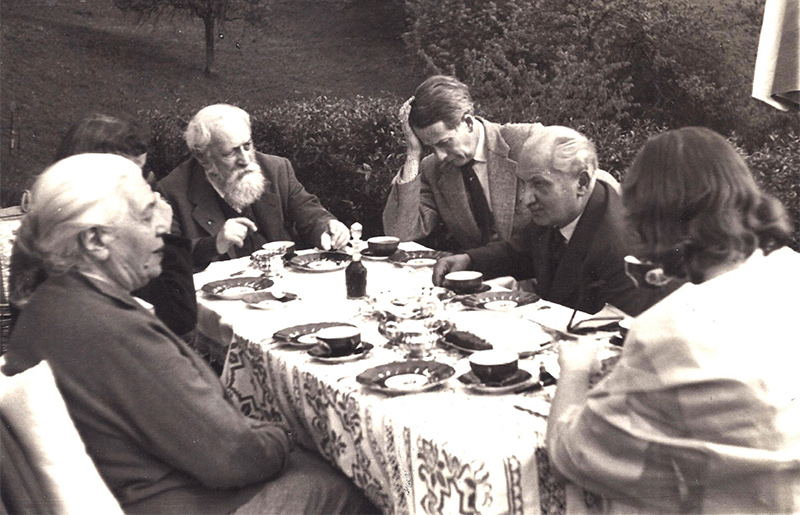

“David Ben-Gurion, for instance, deeply respected Buber’s intellect, particularly Buber’s reading of the Hebrew Bible, and very much wanted Buber’s approval,” Mendes-Flohr adds. “After Buber’s death, Ben-Gurion was one of the first people to express condolences.”

Mendes-Flohr says that were he alive today, Buber “undoubtedly would have been deeply distressed about the political situation in Israel.”

“Before his death in the 1960s Buber was already distressed with what he saw as the establishment of the State of Israel through violence, assertion, and the flight of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their ancestral homes in order to make room for ,” says Mendes-Flohr. “Buber felt that was a cardinal error, and it cast a deep moral strain on the Zionist project.”

Mendes-Flohr admits that a certain amount of nuance and historical background is also needed to address this issue within its intricate context. Buber’s concern about the confrontation with an Arab population in Palestine took place against a broader historical backdrop of 20th century European history. He notes that Judaism was facing ferocious anti-Semitism often regarded as apocalyptic, and which indeed proved to be with the culmination of the Holocaust.

The biographer admits that in such imminent historical circumstances Buber understood the urgency of political Zionism was a natural concern, despite the personal, moral, political and spiritual reservations he may have had to the State of Israel more broadly.

“Buber always sought to ask, ‘How can we balance the deepening ferocity of anti-Semitism without abandoning the spiritual and cultural task of Zionism?’” Mendes-Flohr says. “He lived with that tension between the political urgency of Zionism — to establish a safe dwelling for the Jewish people — while also not losing sight of more spiritual vocation and mission.”